South Bulletin 80, 30 June 2014

Major issues on world economy and WTO, FTAs, IPRs debated at South Centre Conference

This issue of South Bulletin focuses on the South Conference on the global economy and the state of multilateral negotiations. The conference addressed major issues on the world economy, trade, intellectual property, climate change and sustainable development. The main issues at the conference included:

- North’s policies affecting South’s economies

- Africa’s acute problems with EPAs

- The post-Bali agenda at the WTO

- Strong resistance to FTAs & new issues

- Addressing the commodities issue

- Paradigm shift taking place in thinking on IPRs

- Climate change and indigenous rights

The Bulletin also reports on the 32nd Board and XVth Council of Representatives meetings of the South Centre and the events that were held in conjunction with them.

There is also a report on a special tribute seminar to commemorate the life and intellectual legacy of Dr. Gamani Corea, former Chair of the South Centre Board.

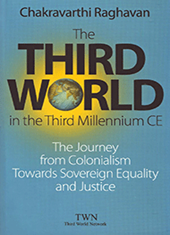

Two books were also launched during this occasion. During the reception hosted by the South Centre, Editor Emeritus of the South-North Development Monitor (SUNS) and trade expert Chakravarthi Raghavan’s book The Third World in the Third Millennium CE was launched. During the conference, Emeritus Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and Vice Chair of the South Centre Board Deepak Nayyar’s book Catch Up was launched.

To download the entire South Bulletin, please click here. To read individual articles, please see below.

The Board and Council of the South Centre Hold Meetings in Geneva

The month of March saw the South Centre organising a series of events centred around the 32nd meeting of its Board and the XVth meeting of its Council of Representatives, and included a reception for the Member States and a holding of a South Conference on the global economy and the state of multilateral negotiations. A book launch of trade expert Mr. Chakravarthi Raghavan’s book The Third World in the Third Millennium CE and a special tribute seminar in commemoration of the life and intellectual legacy of Dr. Gamani Corea, former Chair of the Board of the South Centre, also took place. In addition, the South Centre bade farewell to Prof. Deepak Nayyar, Vice Chair of the Board, as his term finishes.

Board meeting and reception

Under the chairmanship of the South Centre Board Chair H. E. Mr. Benjamin William Mkapa, former President of the United Republic of Tanzania, the Board of the South Centre held its 32nd meeting on 17 and 18 March 2014 in Geneva. The Board is the governance body of the South Centre that is tasked to review and approve the work programme and the annual budget of the South Centre, and report on these to the Council of Representatives of the Member States of the South Centre which serves as the highest policymaking body of the organisation.

At its 32nd meeting, the Board reviewed the Centre’s activities that were undertaken in 2013 and approved the work plan for 2014. The Board also reviewed the Centre’s financial status and approved its budget for 2014. The Board also agreed to nominate two new Board members. They are Dr. Omar El-Arini from Egypt, former Chief Officer of the Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol and current Senior Advisor to the government of Egypt in the area of environment and elected member of the Board of the Green Climate Fund, representing Africa for the period 2012-2015, and Mr. Yang Wenchang from China, current President of the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs and former Vice Foreign Minister of China (1998-2003), former Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and former Ambassador of China to Singapore. They also agreed to extend Dr. Charles Soludo’s term as a Board member for another three years.

The African Union (AU) Trade Commissioner, H. E. Mrs. Fatima Haram Acyl, paid a visit to the South Centre during the Board meeting and gave a talk on the AU’s view on trade. The South Centre decided to have stronger cooperation with the AU.

A reception was hosted by the South Centre at its office on 17 March. It was attended by the Board members, ambassadors and senior officials from the permanent missions of the Member States of the South Centre and other developing countries, and of international organisations and NGOs based in Geneva. At the reception, Chairman Mkapa stressed the crucial importance to the South Centre of the continuing support being provided by its Member States and other developing countries in enabling the South Centre to carry out its mandate to strengthen South-South solidarity and unity in today’s global context. Chairman Mkapa expressed his appreciation for the work of the Board and of the Secretariat.

The AU Trade Commissioner also spoke at the reception and said that after the liberalization of Africa, the struggle now is economic, and there what we are really talking about is trade. She said that Africa has very huge challenges ahead, particularly the negotiations, for example, the Economic Partnership Agreements, the bilateral investment treaties, the WTO and post-Bali and that as developing countries, we need to stand together, speak with one voice and really mean it, and ask ourselves how do we fight and ensure our interests are preserved. She also expressed appreciation for the help the AU as well as the African countries are receiving from the South Centre. They are very proud of the Centre’s work and look forward to working more with the Centre including in other areas such as mining, investment, and intellectual property rights.

During the reception, a book launch of The Third World in the Third Millennium CE, The Journey from Colonialism Towards Sovereign Equality and Justice by Chakravarthi Raghavan, Editor Emeritus of the South-North Development Monitor (SUNS) and trade expert, was held (see next article in this bulletin).

Prof. Deepak Nayyar, Vice Chair of the South Centre Board, had come to the end of his term. The South Centre bade him farewell and expressed its gratitude to his service during the reception. Prof. Nayyar served at the South Centre Board for nine years, his last three years as Vice Chair. Chairman Mkapa conveyed that he was a very diligent member of the Board and that as Vice Chair he had made his tasks lighter. Prof. Nayyar was in charge of the Finance Committee and the Chair articulated that he had done very well in that job. He also emphasised that Prof. Nayyar was a great thinker – a South, economic, and social thinker. Prof. Nayyar expressed that serving at the Board of the Centre has been a source of great joy and satisfaction. He said that the last five years, in retrospect, was incredible, in restoring the confidence in the South Centre of the stakeholders and that this was a product of teamwork. He is leaving with a sense of comfort that this institution has grown stronger.

The South Centre also bade farewell and conveyed its thanks to Board member Minister Li Zhaoxing, who was also very instrumental for the organisation.

Meeting of the Council of Representatives

The 15th meeting of the Council of Representatives of the Member States of the South Centre took place on the afternoon of 18 March at the Palais des Nations, and was attended by the ambassadors and senior officials of the Member States. It was chaired by the Convenor of the Council, Ambassador Abdul Minty of South Africa.

The Council heard the report of Mr. Martin Khor, Executive Director of the South Centre Secretariat, on the Centre’s activities and financial situation. The Convenor and the Chairman of the Board encouraged all Member States to ensure their continued financial support to the Centre as the best means for strengthening the Centre’s ability to support the South in various multilateral forums.

Many representatives of the South Centre’s Member States spoke in appreciation of the Centre’s work and its activities during 2013, particularly in terms of the assistance provided by the Centre to developing countries in negotiations at the WTO, WIPO, UNCTAD, UNFCCC, WMO, and on issues relating to the global economy, the global financial crisis, sustainable development, health and the right to development. The research output of the Centre was appreciated by the representatives for their quality, usefulness, and ability to provide developing country perspectives on global issues. The Member States also appreciated that the Centre’s financial situation had improved, with an increased operational surplus in 2013 following on from the operational surpluses generated in 2009-2012. Among the Member States whose representatives spoke were Algeria, Barbados, China, Cuba, Ecuador, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Jamaica, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Africa, Tanzania, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

The Chairman of the Board then put forward for the consideration of the Council of Representatives Dr. Charles Soludo’s second three-year term of membership of the Board and the Board’s nomination of Dr. Omar-El Arini and Mr. Yang Wenchang to serve on the Board of the South Centre. These were unanimously approved by the Council.

Launch of Raghavan’s new book

By Kanaga Raja

By Kanaga Raja

The South Centre on 17 March launched the publication ‘The Third World in the Third Millennium CE’, written by Mr. Chakravarthi Raghavan, Editor Emeritus of the South-North Development Monitor (SUNS).

The launch took place during an evening reception at the Centre, which was attended by some South Centre Board members as well as ambassadors and other officials.

The book, subtitled ‘The Journey from Colonialism Towards Sovereign Equality and Justice’, is the first of two volumes and is published by the Third World Network.

At the South Centre reception, Mr. Martin Khor, the Executive Director of the South Centre, introduced Mr. Raghavan to the assembled audience, saying that Mr. Raghavan had been associated with the South Centre long before the South Centre was even born.

He noted that Mr. Raghavan had brought to the attention of the then South Commission, whose Secretary-General was Dr. Manmohan Singh at the time (and who is the former Indian Prime Minister), that something was going on in Geneva called the Uruguay Round.

Mr. Khor recalled that Mr. Raghavan had written a 20-page paper on this subject that was later publicised by the Third World Network.

(The paper was later expanded into the book ‘Recolonization: GATT, the Uruguay Round & the Third World´.)

He went on to say that Mr. Raghavan has been writing about multilateral negotiations, not only the GATT and the World Trade Organization (WTO), but also on many other issues.

Referring to Mr. Raghavan’s book, Mr. Khor said that this is the first volume of a compilation of the many papers that Mr. Raghavan had written over the past 20 to 30 years.

He noted that the foreword to the book was written by Mr. Rubens Ricupero, a South Centre Board member and a former Secretary-General of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (from 1995-2004).

In launching the publication at the reception, Professor Deepak Nayyar, Emeritus Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University and a Member of the South Centre Board, said that he had known Mr. Raghavan longer than has Mr. Ricupero (who had been originally slated to launch the book at the reception but had to excuse himself on account of being unwell on that day).

Prof. Nayyar said that he has known Mr. Raghavan for close to 30 years, adding that he had first met Mr. Raghavan in the early eighties when Prof. Nayyar had chaired some ‘contentious’ committees on services in Geneva during the Uruguay Round.

“May I say that Mr. Raghavan is a most unusual person. He is a person who has a belief system and a courage of conviction, and a moral strength that is increasingly difficult to find these days in almost every walk of life but particularly in the world of journalism,” he said.

Prof. Nayyar said he remembered vividly the early days when Mr. Raghavan had started the SUNS – and as Mr. Ricupero has said in the foreword to the book – “it was an idea in the head and a typewriter in hand” in a small cubicle in the Palais des Nations (the UN’s European headquarters in Geneva) where his office was.

He recounted that Mr. Raghavan was banging away at the typewriter producing column after column of rigorous analysis and authentic information about what was happening in the world of multilateral trade negotiations.

“In this world of internet and the information explosion, it’s hard to recognise that this made an enormous difference,” said Prof. Nayyar.

Prof. Nayyar then said that he had first met Mr. Ricupero soon after he came to Geneva as Brazil’s Ambassador to the GATT, and Mr. Ricupero had told him – as have many of his colleagues who were ambassadors such as Ambassadors S. P. Shukla and Bhagirath Lal Das – that Mr. Raghavan was in a sense a ‘tutor’ to all the ambassadors to the GATT.

According to Prof. Nayyar, this was because Mr. Raghavan had a kind of accumulated knowledge and internalised understanding which professional diplomats who had just arrived in Geneva found a wonderful reservoir to draw upon.

“And he was a fantastic support to all of them,” observed Prof. Nayyar, noting that Mr. Ricupero had also pointed that out in his foreword to the book.

Prof. Nayyar also recounted a story which he said he had not told Mr. Raghavan till now, when both he and former US Trade Representative Clayton K. Yeutter (1985-1989) were at a small brainstorming session somewhere in Austria, where Yeutter had said to him over a drink in the evening that ‘you know, I hate Ambassador Shukla’s guts. He’s a real nuisance to me, but I would give twenty of my best people to have one Shukla on my side.’

Prof. Nayyar recalled Yeutter as also saying about Mr. Raghavan that ‘I hate Raghavan’s guts. He is a real nuisance but he has a capacity to tell the truth, to tell it clearly and to tell it firmly’.

Prof. Nayyar said that Mr. Raghavan in that sense is very unusual, noting that standards (in the world of journalism) “have slowly but surely deteriorated” in terms of morality, beliefs and convictions, but that the journalist’s task is much more difficult because it is about writing contemporary history.

In this context, Prof. Nayyar noted that the historian Eric Hobsbawm, who passed away not so long ago, used to write the history of his own times.

“In many ways, I think Raghavan’s perceptive writings over the years – and I’m sure these volumes will bring it to light – have had a kind of clairvoyant contact because they foresaw some things to come.”

“For that, I think much credit is due,” said Prof. Nayyar, adding, however, that this is not the credit Mr. Raghavan will get.

The credit he will get, as Mr. Ricupero says (in his foreword), is the esteemed gratitude and admiration of those friends or professional colleagues who have known him for a lifetime, for the person that he is, not just for his professional qualities but for his human qualities (as well), said Prof. Nayyar.

He ended with an epitaph from Mr. Ricupero’s foreword to the book in that Mr. Raghavan “has helped us rescue knowledge from the world of information and wisdom from the world of knowledge because he is able to see the wood from the trees.”

Dr. Yilmaz Akyuz, Chief Economist at the South Centre and a former chief economist of UNCTAD, recounted that when he was at UNCTAD, he was following in the publication SUNS not only what was happening in Geneva but also at UNCTAD, and that in his writings, Mr. Raghavan often commented particularly on (UNCTAD’s flagship publication) the Trade and Development Report.

“And from time to time we could find things which we didn’t realise that we [had] said,” Dr. Akyuz said, adding that in discussions (among friends), it was asked, ‘did we really say that? This is quite interesting.’

He said that Mr. Raghavan was taking the report and putting the natural consequences – “perhaps we were too shy to do it being in the UN bureaucracy” – and in this process, they learned a lot not just in terms of analysis and events but also in terms of the politics of the international system.

Mr. Raghavan then spoke and in thanking the audience, he remarked that fortunately God had given him a natural tan, hence, he could not blush.

“I don’t think I have done anything very extraordinary at least not very different from what people of my generation were taught or we learned,” he said, pointing out that he grew up in colonial India, in a place called Madras, where as he grew up he came into contact with some big personalities (of the Independence movement).

Pointing out that he was a physics graduate and that he did not know anything at all about economics and was in fact trying to qualify in actuarial science, Mr. Raghavan said that he had met Mahatma Gandhi and spent 10 days with him at a camp in 1945 and that had changed his entire outlook in life, and eventually led him to come to Geneva.

As far as his book is concerned, Mr. Raghavan said that the editors (at Third World Network) had put together “what we thought from all my writings, things that may be of some more lasting value than the ephemeral daily reports of news and views.”

He noted that most of the material was typewritten and had to be digitalised, and that when this was done, it was found that there was a need to connect the past with the present, otherwise, it did not make any sense in merely reporting what had happened in Geneva or in New York between those years that were covered in the book.

It was also decided that trade was to be separated from everything else, because “trade itself is a peculiar animal, and we don’t know what kind of an animal it has come from and where it is going to go.”

Mr. Raghavan recalled that it took him quite a while to write the connecting history, asking ‘how do you write what happened before the war’, as he did not write before the war.

He said that in India, he did not write under his own name, and that the first time he wrote under his own name was when he came to Geneva and that it was translated and published in Spanish.

“And I suddenly became a very famous person in Latin America but not even in India.”

Mr. Raghavan further said that he tried to connect the past with the present and he did look up and as far as possible, provided footnotes so that people can also look at it and see whether what he was saying was correct or whether he was just bluffing.

He had also tried to provide a different narration. He explained later that there were two kinds of narration of the past. One was a paternalistic view of imperialism and colonialism and the attempts of metropolitan powers to “civilize”, modernize and improve conditions of people and bring them up to self-governance. The other was the Niall Ferguson variety of justification and praise of imperialism.

He said that he did what he could from a different perspective, merely in order to tell that it is not as if people in the past have not lived through this and “those who forget the past cannot have a future or rather cannot influence the future. That is the one particular aspect of life we all need to remember.”

He expressed hope that the audience would enjoy his book and draw some benefit out of it.

In any event, Mr. Raghavan concluded, as the saying goes in his part of the world: ‘if you are prepared to discard what I have said [as] utter nonsense, then you should not hesitate to say so.’

Kanaga Raja is a Geneva-based journalist who writes for the South-North Development Monitor (SUNS).

South Centre Conference: The Global Economy and State of Multilateral Negotiations

The South Centre convened its annual conference entitled “The Global Economy and State of Multilateral Negotiations”, on the 19th of March 2014 at the Palais des Nations in Geneva. The conference served as an opportunity to reflect on the state of the South and the world economy through two major sessions; one was dedicated to discussing the state of the global economy and another addressed trade and development issues, including the state of multilateral negotiations.

Reports on the Conference written by Kinda Mohammadieh

Chairman Benjamin W. Mkapa’s Opening Speech

On behalf of the South Centre, I welcome you to our conference, being held in conjunction with the meetings of the Council and Board of the Centre.

The themes of the conference are the global economy, which will be discussed this morning, and the state of multilateral negotiations, in the afternoon.

We have chosen these topics because the Centre believes that the global economic conditions and how they affect developing countries is now a crucial issue that will be of immense importance to our policy makers and political leaders. On the other hand, the South Centre’s bread and butter activity is to help developing countries with multilateral negotiations, and a review of some of these negotiations is very topical.

We have assembled some eminent experts of the South to address these issues, and we are very happy that you have assembled here to discuss what they have to say.

The global economy has not really recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. Indeed, the South Centre predicted that when the Western economies begin their recovery, the developing countries would be in even bigger trouble. Reality is now showing that our prediction has been correct.

The developed countries have made policy choices during their crisis that in our view were not appropriate either for their own economies or for the global economy. Their policies are hurting the developing countries. For example, due to their easy money policies, a lot of speculative capital went into the developing countries. This boom created problems including inflation, asset bubbles, and exchange rate appreciation that reduced our export competitiveness.

Now that the US easy money policy is tapering or being reduced, the reverse problems are evident. Capital is flowing out of developing countries back to the US and Europe, and currencies are depreciating, making it harder to service external debt. The balance of payments deficits of some countries are widening. The prospects for commodity prices are not bright. The GNP growth rate has reduced.

We are waiting eagerly to listen to our own South Centre chief economist, and to the many other experts in the first panel. Can developing countries do anything to get the developed countries to correct their policies? Can developing countries do something to defend themselves if the misguided policies of the West continue? How will developing countries be affected and what can they do?

The second panel discussion is equally interesting. The crucial negotiations now taking place are about trade, about intellectual property, and about the post-2015 development agenda and the SDGs. We have eminent experts to address the WTO’s Bali outcome and the post-Bali agenda. We also have experts who will discuss the commodities issue, and the issue of climate change from indigenous peoples’ perspective.

As for myself, I believe that the Economic Partnership Agreement which the EU is trying to get African countries to agree to, is the most critical trade and negotiations issue facing Africa. If the EU’s model is accepted, it would cause immense damage to our agriculture, industry and development prospects. It will also make it very difficult if not impossible to achieve effective economic integration within the African continent, which has been a dream of our political leaders since independence.

I understand that in Geneva, the WTO negotiations have revived, and with this revival come many opportunities and dangers. The most important principle is that the development dimension and objective of the Doha Development Agenda must be respected and adhered to not only in rhetoric but in the outcomes. Otherwise it is better to continue fighting for it, than to give in to the developed countries, just because we want to conclude the negotiations.

On the SDGs and post-2015 development agenda, the South Centre has done a lot of work in this area, and I look forward to listening to the discussion on this, as well as on commodities.

I wish all of you good discussions at this conference, which I now declare opened. Thank you.

North’s policies affecting South’s economies

Dr. Yilmaz Akyuz, chief economist of the South Centre, delivered the keynote speech of the first session.

Dr. Yilmaz Akyuz commenced his keynote presentation by noting that, since the onset of the crisis, the South Centre has argued that policy responses to the crisis by the EU and the US suffered from serious shortcomings that would delay recovery and entail unnecessary losses of income and jobs, and also endanger future growth and stability. He reminded the participants that while his analysis indicated that developing countries could benefit in some respects in the short-term, notably from the policy of easy money, he had highlighted that they would be exposed to serious shocks in the future.

Dr. Akyuz noted that there is little to add to what was previously said, except that these arguments are no longer wild guesses or prognostications, but hard reality. He called for reassessing the situation and thinking of ways to respond to a renewed turmoil.

Dr. Akyuz highlighted that the world economy is not in a good shape, despite cautious optimism from the IMF. Six years into the crisis, which was declared recession at the beginning of 2007, the US has not fully recovered, the Euro zone has barely started recovering, and developing countries are losing steam, Akyuz noted. There is fear that the crisis is moving to developing countries, he added.

Dr. Akyuz noted his concern in regard to the longer-term prospects for three main reasons. First, the crisis and policy response aggravated systemic problems, whereby inequality widened. Inequality is no longer only a social problem, according to Akyuz, but also presents a macroeconomic problem. Inequality is holding back growth and creating temptation to rely on financial bubbles once again in order to generate spending. Secondly, global trade imbalances have been redistributed at the expense of developing countries, whereby the Euro zone – especially Germany – has become a deadweight on global expansion, Akyuz added. Third, systemic financial instability remains unaddressed, despite the initial enthusiasm in terms of reform of governance of international finance, and in addition there are new fragilities added due to the ultra easy monetary policy.

Moreover, China is not only moving to slower growth but can also face hard landing due to the debt overhang created by its response to fallouts from the crisis, Akyuz added. According to him, the situation of China is becoming a problem rather than a solution. Furthermore, Akyuz was of the opinion that developing countries have not responded to the situation properly, thus often failing to manage booms in commodity prices and capital flows, which made them vulnerable to financial shocks.

The policy response to the crisis has been an inconsistent policy mix, including fiscal austerity and ultra-easy monetary policy, Akyuz explained. While the crisis was created by finance, the solution was still sought through finance, he cautioned. Countries focused on a search for a finance-driven boom in private spending via asset price bubbles and credit expansion. Fiscal policy has been invariably tight. The ultra-easy monetary policy created over USD 1 trillion fiscal benefits in the United States, which was more than the initial fiscal stimulus, Akyuz noted. The entire initial fiscal stimulus in the United States was limited to USD 800 billion.

Akyuz indicated that there was reluctance to remove debt overhang through comprehensive restructuring (i.e. for mortgages in the United States and sovereign and bank debt in the European Union). Thus, the focus was on bailing out creditors, he noted. There was also reluctance to remove mortgage overhang and no attempt to tax the rich and support the poor – particularly in United Kingdom and the United States – where marginal tax rates are low compared to continental Europe, Akyuz added. There has been resistance against permanent monetization of public deficits and debt, which according to Akyuz does not pose more dangers for prices and financial stability compared to the ultra-easy monetary policy.

Akyuz noted that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and central banks have been releasing evidence that without the ultra-easy monetary policy the crisis would have been deeper. Yet, there is no discussion of an alternative policy mix, including debt workouts and fiscal stimulus nor attempts to discuss what outcome could have resulted from such alternative interventions, he stressed.

Akyuz reviewed the situation in various regions. According to him, the situation in the United States has been better than other advanced economies. The United States dealt with the financial but not with the economic crisis, whereby recovery has been slow due to fiscal drag and debt overhang, he explained. Akyuz noted that employment is not expected to return to pre-crisis levels in the United States before 2018.

As for the Euro Zone, Japan, and the United Kingdom, Akyuz noted that all had second or third dips since 2008. None of them have restored pre-crisis incomes and jobs, Akyuz added. The Euro Zone has been struggling to turn the corner from recession to recovery, according to the IMF. Akyuz highlighted the prospects of seeing the Euro Zone heading into deflation. He highlighted the weak demand, which stands at 5% below 2008 levels, including 15% lower than 2008 levels in the periphery countries. Financial stress has eased in the Euro Zone, although there is still high fragility and more turmoil could be possible in 2014, Akyuz noted. According to him, the recovery has been too weak to generate jobs and the jury is still out on the situation of the Euro.

Advanced economies, including the United States, European Union, and Japan have witnessed potential output constantly falling below usual trends because of the lack of investment and declines in labor participation, according to Akyuz.

He added that inequality has been widening, whereby the top 1% in the United States captured the entire income gains in 2009, and wealth has been further concentrated. Bank profits soared and Wall Street bonuses have been back to historical highs, while the ‘too-big-to-fail’ banks are today bigger, Akyuz added.

In the Euro Zone, the periphery has joined Germany in the trend of wage suppression, Akyuz noted. Real wages in the United Kingdom are not expected to go back to pre-crisis levels before 2020 even with accelerated growth, he added. Downward trend in the share of wages has been accentuated, Akyuz highlighted, whereby the threat of deflation due to under-consumption has been rising. Until 2008, deflation was avoided thanks to bubbles in the United States and the European Union and several emerging economies. These bubbles have led to deepening fragility and crisis. Yet, what is witnessed today is a temptation to rely once again on asset and credit bubbles for growth, Akyuz added. He noted that Lawrence Summers and Paul Krugman argue that there is a constant demand gap in the United States, which would face circular stagnation without bubbles that have been driving growth since the 1980s.

Akyuz addressed trade imbalances noting that they have not been removed, but redistributed. East Asian surplus dropped sharply and Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa moved to large deficits, Akyuz noted. Developing countries’ surplus fell from USD 720 billion to USD 260 billion. On the contrary, advanced economies moved from deficit to surplus, whereby the United States’ deficits fell and the Euro Zone moved from USD 100 billion deficits to USD 300 billion surplus.

Of three main surplus countries, Japan started running deficits from mid-2013 while China’s surplus declined sharply after 2007, Akyuz added. Germany replaced China with a surplus of 7% of GDP. Unlike in China where strong exports complemented buoyant domestic spending, in Germany exports offset sluggish domestic demand, Akyuz explained. The German surplus has been falling against that of the Euro Zone periphery, Akyuz explained, but rising against the rest of the world. Competitive disinflation (i.e. internal devaluation), lid on wages and domestic demand, and deflationary bias are witnessed across the world economy and not just in the Euro Zone, he added.

Akyuz noted that until recently the impact of easy monetary policy has been felt mainly in asset markets, stocks hitting historical highs without much wealth effect, and in surges in capital flows and bubbles in emerging economies. But household borrowing in the United States has been rising again, Akyuz noted, whereby the last quarter of 2013 saw the largest increase in household debt in the United States since 2007.

Ultra-easy monetary policy is still on, Akyuz stressed, whereby interest rates are still unchanged. He clarified that tapering is not tightening or exiting from the ultra-easy monetary policy. Exiting this policy would mean reducing and normalization of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and shortening maturity of assets held by the Federal Reserve. Yet, there is still uncertainty about normalization of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. Akyuz stressed that it would be difficult for the Federal Reserve to exit without disruption, or to maintain its policy without creating bubbles. The longer the ultra-easy monetary policy is kept the more abrupt the exit would be, Akyuz noted, which creates a dilemma for emerging economies.

Akyuz highlighted that as tapering comes to an end and the Federal Reserve stops buying further assets, the attention will be turned to the question of exit, normalization, and the expectations of increased instability of financial markets for both the United States and the emerging economies. This exit will also create fiscal problems for the United States, he added. For as bonds held by the Federal Reserve mature and quantitative easing ends, long-term interest rates will rise and fiscal benefits of ultra-easy monetary policy would be reversed.

In regard to the South, Akyuz noted that the initial resilience of developing countries could be associated with three main reasons, including: the quick recovery of capital flows; the Chinese massive investment package that gave a boost to commodity exporters; and the countercyclical response in developing countries that was made possible by improved fiscal balances during pre-crisis expansion, thus allowing to shift focus to domestic demand.

However, developing countries have lost steam as recovery in advanced economies remained weak or absent due to the fading effect of countercyclical policies and the narrowing of policy space, Akyuz explained. He also added that China could not keep on investing and doing the same thing. Another factor contributing to the change of context in developing countries has been the weakened capital inflows that became highly unstable with the deepening of the Euro Zone crisis and then Federal Reserve’s tapering. Several emerging economies have been under stress as markets are pricing-in normalization of monetary policy even before it has started, Akyuz pointed out.

Akyuz added that the external financial vulnerability of the South is linked to developing countries’ integration in the global financial markets and the significant liberalization of external finance and capital accounts in these countries. These include opening up securities’ markets, private borrowing abroad, resident outflows, and opening up to foreign banks. While developing countries did not manage capital flows adequately, the IMF did not support in this area, tolerating capital controls only as a last resort and on temporary basis.

Akyuz added that while sovereign debt in emerging economies is leveled off as proportion of GDP, foreign presence in local credit and bond markets have been increasing. Private borrowing abroad has been massive in China, India, and Brazil, while corporate bond issues and interbank borrowing have been at record levels in these countries, Akyuz noted. Many portfolio (carry-trade) investors in emerging economies are leveraged, he added, all of which are highly susceptible to swings in the United States’ monetary policy.

Several deficit developing countries with asset, credit, and spending bubbles are particularly vulnerable, Akyuz stressed. Countries with strong foreign reserves and current account positions would not be insulated from shocks, as seen after the Lehman crisis. When a country is integrated in the international financial system it will feel the shock one way or another, although those countries with deficits remain more vulnerable, Akyuz stressed.

In regard to policy responses in the case of a renewed turmoil, Akyuz called for avoiding business-as-usual, including using reserves and borrowing from the IMF or advanced economies to finance large outflows. The IMF lends not to revive the economy, he noted, but to keep stable the debt levels and avoid default. He also argued against adjusting through retrenching and austerity.

Akyuz called for finding ways of bailing-in foreign investors and lenders, and using exchange controls and temporary debt standstills. Akyuz stressed that the IMF should support such approach through lending into arrears.

More importantly, Akyuz underlined, the Federal Reserve is responsible for the emergence of this situation and should take on its responsibility and act as a lender of last resort to emerging economies, through swaps or buying bonds as and when needed. These are not necessarily more toxic than the bonds issued at the time of subprime crisis, Akyuz noted. He was of the opinion that the United States has a lot at stake in the stability of emerging economies.

Akyuz also called for addressing systemic issues, including governance of international finance, which was addressed in the Outcome Document of the 2009 UN conference on the World Financial and Economic Crisis and its Impact on Development. Akyuz called upon developing countries to put this issue on the Post-2015 agenda.

Effects of crisis & recovery on South countries

Dr. Deepak Nayyar, emeritus professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University and member of the South Centre’s board, addressed the situation of developing countries in the aftermath of the financial crisis, while focusing on their real economy variables. He noted that developing countries on the whole have fared better than industrialized and transition economies in the aftermath of the crisis. Yet, some high-income emerging economies that depend on exports to the United States and the European Union were hard hit, Nayyar noted. In contrast some large developing countries did not fare badly. For example, the growth performance of Sub-Saharan Africa and some least developed countries has been robust.

Dr. Nayyar explained that the impact of the global crisis was less adverse due to four factors, including the robust initial conditions before the crisis, specifically macroeconomic stability, moderate inflation, and large foreign exchange reserves combined with economic growth. All of these factors provided for structural stability at macro and micro levels, Nayyar noted. Other factors include the fact that the financial liberalization was somehow restrained in many developing countries, safety nets for the poor and vulnerable were in place, and domestic consumption was helpful in many of the large economies.

Professor Nayyar noted that the economic recovery of most developing countries was faster for three reasons. First was the fact that they adopted expansionary countercyclical macroeconomic policies, which have been unusual till then in the developing countries. Their response to the crisis was effective and fast. Second, the size of the home market made a difference, and the increase in demand came from segments of the population with a high propensity to consume. Third, the financial sectors were less fragile and more regulated than elsewhere, and did not absorb scarce resources from stimulus packages or bailouts. Easy monetary policies in these countries meant lending to the real sector, Nayyar underlined.

Generalizations are difficult when the underlying factors are different, Nayyar cautioned. Yet, there is little doubt that initial conditions, policy responses, and domestic demand shaped resilience, Nayyar added, while prudence in deregulation and liberalization of financial sectors made a difference along with fiscal space available to governments.

The significant increase in the share of developing countries in world income and trade meant that there were external resources and markets available to them, other than the industrialized countries.

This performance of several emerging economies led some analysts to the wrong conclusions, whereby they proposed that these countries could drive the recovery in the world economy, Nayyar cautioned. Yet, the ‘decoupling’ theory does not hold, Nayyar stressed. It is clear that these countries cannot turn into engines of growth for the world economy, and none of these countries could provide resources for development, finances for investment, or needed technologies as Britain did in the 19th century and the United States did in the 20th century, he added. Thus, the prospects and pace of recovery in the world economy depends on the pace and nature of recovery in the industrialized world, particularly in the United States.

Nayyar noted that recovery has been slow, uneven, and fragile, and prospects uncertain. It would seem that the problem has been compounded by the return to orthodox economic policies everywhere, he added. The United States and Japan seem an exception, whereby there is a recovery in output but not much in employment. In the European Union countries, decisions to sharply reduce fiscal deficits are being implemented. Nayyar noted that he sees those approaches as possibly turning out worse than the problem.

Many of the large developing countries, and the so-called ‘emerging economies’ such as Argentina, Indonesia, Turkey, China and others have experienced slowdown in growth attributed to the great recession in the developed economies, Nayyar explained. For China, the slow recovery in the United States and recession in the European Union have been challenging factors, given that exports to those markets were critical for China.

However, the slowdown in other larger developing countries is attributable significantly to their own mistakes, Nayyar stressed. Macroeconomic policies are back to being pro-cyclical, high interest rates have stifled investments, attempts to reduce fiscal deficits have curbed public spending and domestic demand, strong exchange rates to sustain portfolio investment flows have effected export performance, and the dependence on these inflows of capital is currently greater. Nayyar pointed out that given this reality, it is not a surprise that the announcement of the phase-out of monetary easing in the United States is having such strong impact on these economies.

Again, these recent developments have led some analysts to hasty conclusions. In August 2013, Morgan Stanley presented Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey, and India as the ‘fragile five’ economies, for they were too dependent on foreign capital inflows to finance their current account deficits and support their growth. Soon after, an asset management firm in Boston called ‘Fidelity’ coined the term ‘MINTs’, standing for Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey. According to ‘Fidelity’, the ‘MINTs’ are emerging economies with a promising future since the BRICS (i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) were running out of steam. Interestingly, Indonesia and Turkey feature in both groupings. It is clear that such thinking is shaped by the conjecture and framed in the shorter-term perspective, Nayyar stressed.

In the medium-term perspective such thinking is inappropriate, if not misleading, Nayyar stressed. He pointed out that in contemplating the future of the world economy, it is essential to focus on a larger group of developing countries and a longer-term perspective rather than the next quarter or next year. The time horizon to consider should be 2025 instead of 2015, according to Nayyar.

Nayyar underlined that there is much that developing counties can do in terms of correcting their policies; they could redefine macroeconomic objectives and policies to make employment and growth the central objectives rather than focusing on managing inflation. They could also recognize that external markets are at best complements rather than substitutes to domestic markets. They could also begin to correct market fundamentalism and recognize the role of the state as critical for recovery and sustained growth.

In regard to the future prospects for larger developing countries, assuming that these corrections are introduced, Nayyar noted that there is potential for growth but with real constraints. The determinants of potential growth in developing countries are a source of good news, according to Nayyar, and in principle these countries could sustain high rates of growth for some time. These determinants include their population size that is large and income levels that are low. Thus, possibilities of growth are greater. Moreover, their high proportion of young people means that the increasing workforce is conducive to growth provided education spreads across society. Furthermore, their wages are significantly lower than the rest of the world, which is an important source of competitiveness.

In practice, the developing world will not be able to realize this potential due to constraints that may differ across space and time, Nayyar cautioned. There are some general constraints such as poor infrastructure, weak institutions, inadequate education, unstable politics, and poor governance. There are constraints that may arise from the process of growth such as economic exclusion, social conflict, and environmental stress. There are other constraints that are external, such as worsening terms of trade, inadequate sources of external finance, restricted market access, possible crisis in the world economy, in addition to other country specific constraints.

Nayyar stressed that developing countries need to introduce correctives in the management of their economies, although this is easier said than done. The biggest challenge lies within, beyond policies and institutions that are the focus of conventional wisdom, Nayyar noted.

Nayyar called upon developing countries to address problems of rising inequalities that could be the dominant constraint on growth in the future. They must ensure that benefits of economic growth are distributed more equally among peoples across and within countries.

Nayyar cautioned that economic growth could not be sustained in the long-term if it does not improve the living conditions of ordinary people. This is the only sustainable way forward because it will enable them to mobilize people for the purposes of development and reinforce the process of growth through a virtuous cycle of cumulative causation, recognizing that there is an interaction between the supply and demand sides. Wages could be seen as costs on the supply side, which is what orthodoxy chooses to focus on, Nayyar noted. But wages are also incomes on the demand side that could drive growth, Nayyar stressed. He called for combining economic growth with human development and social progress.

In this process the real checks and balances come from political democracies. Nayyar concluded that in contemplating the future of developing countries, there is need to concentrate on a larger group of developing countries and not only emerging economies, think of longer-term horizons, and shift the focus from short-term equilibrium to longer-term growth and from the financial sector to the real sector of the economy.

Four scenarios on world economy

Dr. Richard Kozul-Wright, director of UNCTAD’s division on Globalization and Development Strategies (GDSD), commenced his presentation by underlining the likelihood of a much more difficult macroeconomic environment that could face the economies of the South in the medium-term. He was worried that policy makers in the South have been slow to register the kind of changes in the global economy and systemic weaknesses that have been documented by Dr. Yilmaz Akyuz. UNCTAD over the last few years has been critical of the ‘de-coupling mythology’, as he called it, which developing country policy makers themselves have bought into. UNCTAD has been warning that there are hard choices to be made in macroeconomic policies and strategies in the coming years.

Kozul-Wright explained that GDSD’s work identified four broad scenarios facing the world economy:

- The first scenario is a ‘muddling-through’ scenario, which is a continuation of slow growth, driven by efforts to rebalance private sector balance sheets and continuance of fiscal austerity in advanced economies. This is likely to be a world of sluggish investment and persistently high inequalities, continuing to hold back economic potential. This would come with a vague hope that somehow the ‘confidence fairy’ will return to the private sector and reinvigorate private demand in a way that could keep the recovery on track;

- The second scenario is of unsustainable economic growth, essentially faster growth driven by the build-up of debt in the private sector, in which housing booms would be a most likely source of expansion. Injection from those asset booms of demand into the global economy would allow some economies to contemplate export-led recoveries based on which they would be able to revive their growth possibilities. This would be a world in which global imbalances are likely to grow and financial fragilities are likely to re-emerge;

- The third scenario is an instability scenario in which the recovery would be derailed by unruly unwinding of the monetary stimulus, which would likely lead to recurrence of financial shocks and to a combination of currency and banking crises. This would present serious policy challenges in emerging economies, with highly contagious possibilities. The role of the Federal Reserve of the United States and the way it proceeds is pivotal in this kind of scenario;

- The fourth scenario would be a coordinated recovery scenario, in which a combination of monetary and fiscal measures would be used to stimulate demand and to generate more expansionary response to economic adjustments. This would be a scenario in which strong financial regulations are used to reorient the nature of the financial system from asset speculation towards boosting productive capacities in the real economy. Redistributive measures would be used to deal with inequalities that could hold potential destructive implications for the world economy. Such kinds of policies are viable and would have win-win consequences for all parts of the global economy. This was the scenario that the G20 promised to deliver when it was re-established in 2009/2010.

Kozul-Wright underlined that such a scenario of coordinated recovery has been far from what has been seen in practice. It is possible to attribute some success to the G20 in regard to preventing a spiral down of the crisis, and bringing stability to the financial system. But there has been no sign that the G20 operated effectively to bring about a broader effective recovery, he stressed.

This situation begs the question on why this kind of coordinated response has failed to materialize. UNCTAD attributes that to four reasons, Kozul-Wright explained. First factor is the persisting dominance of unregulated finance in shaping the larger policy environment. Most reforms to the financial system have been cosmetic and in many instances non-existent. Second factor is the heavy reliance on monetary policy of unconventional nature, which restricted the policy options necessary for a balanced and coordinated response. Third factor is the continued dominance of the US dollar at the same time that the US has essentially forfeited its leadership role in the global economy. Fourth factor is that South-South cooperation, which has been flagged as a new hope for development in terms of coordinating efforts in the global economy, has yet to provide a meaningful alternative, both in terms of policy coordination in the South and in terms of a wider model for global policy coordination. Despite the optimism that many have in regard to South-South cooperation, it would be naïve to consider that as currently practiced it offers a serious alternative, Kozul-Wright noted.

Dr. Kozul-Wright stressed that the onus is much more on developing country policy makers to rethink their policies and pursue more selective and strategic policies, including better mobilization of domestic resources. He added that in the case of Latin American and African economies that have been heavily dependent on external flows, there is clearly a need to re-orient policies to focus on internal markets as drivers of demand.

Dr. Kozul-Wright stressed the importance of limiting dependence on external markets, while increasing wages as engines for growth. In this regard, Kozul-Wright made reference to interventions such as minimum wage legislation and income policies. He also stressed the importance of raising public spending and public investment, and the ongoing need for industrial restructuring, along the need to revisit technology policies, and the role of development banks as an important source of credit expansion for longer-term affordable credit.

Dr. Kozul-Wright underlined that the Post-2015 agenda does open up real possibilities to articulate such kind of strategies in the multilateral context. Yet, he argued that at this stage developing countries have a lot of homework to do in order to ensure that these issues galvanize their positions in New York, since many of these issues are still not on the radar of developing countries’ negotiating positions in that forum.

The Latin American situation

Dr. Humberto Campodonico, professor at the National University of San Marcos in Peru, commenced his presentation by noting the lack of a unified macroeconomic response to the crisis by developed countries, leading the world to face the prospects of another financial and economic crisis.

Dr. Campodonico tackled the ‘de-coupling thesis’ that was put forward in 2006/2007/2008, including by the IMF, which assumed that the newly industrialized countries (i.e. the BRICS) could take the relay when the developed countries were faltering.

Dr. Campodonico noted that in a globalized world one cannot speak of complete decoupling. What it essentially means, he added, is that a group of economies move from dependence on other economies, and have new engines of growth different from the old engines. He noted that the consequences of the lack of unified response to the macroeconomic crisis and the implications left on the BRICS countries and others is a clear demonstration that de-coupling has not been the case.

In regard to the role of the United States, he noted that today there is no hegemony from one economic power anymore. The world has witnessed such hegemony in 1944, when the Bretton Woods system was created, Campodonico noted, and the world economy functioned with this drive during 35 years. Yet currently the global context reflects a lack of such hegemonic forces. On the political side, Campodonico referred to the cases of Ukraine, Syria, and the drive of China, which according to him reflect a lack of such hegemonic force. He also referred to the economic arena, where he reflected on the situation at the WTO and in the Doha Round. He noted that when there were disputes between the BRICS countries and the United States, European Union, and Japan at the WTO, the move was towards free trade agreements where WTO-plus rules have been pushed, including for example the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Yet, this cannot be a solution on the longer term, Campodonico stressed.

After the 2009 UN Conference on the World Financial and Economic Crisis, the policy proposals addressed there have not been fully taken on, Campodonico cautioned. The US is not giving the IMF support in order to assume the role of lender of last resort.

Campodonico discussed the context in Latin America, where he highlighted the divide between the free trade and market policies adopted by the countries of the Pacific Alliance (Chile, Columbia, Mexico, and Peru) in comparison to what are called ‘Atlantic policies’ involving Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina and others. The latter adopted more development-focused policies directed towards domestic markets and South-South trade, he explained. This, according to Campodonico, is a confrontation that extends beyond economic policies and involves geo-political aspects.

Another issue raised by Dr. Campodonico was the growing debt of private corporations. He noted that Latin America’s problems during the 1980s were mainly due to external public debt. Yet today, numbers show that private corporate debt is very high. He referred to new data released by the Financial Times, which shows for example that Peru’s external private debt has grown from 7% of GDP to 14.2%, which is bigger than external public debt. That is the case in other Latin American countries.

Campodonico noted that if tapering of the US ultra-easy monetary policy begins, and financial flows falter, and interest rates rise, the outcome could be problematic. He explained that the problem would be limited in the case of mining companies or other companies trading in international currency compared to the case of companies selling in the local markets, whereby the mismatch will be very hard to cover. There is very little data on these aspects given that the debt is in the private sphere, Campodonico added.

Dr. Campodonico noted that governments in Latin America considered that current account surpluses and solid fiscal positions would help them be shielded against systemic risk. Yet, these surpluses could evaporate very quickly, he stressed, especially that some of them are not current account reserves but borrowed money, including cash reserves accumulated at banks.

Dr. Campodonico added that Latin America has witnessed improvements in terms of trade like nothing seen since twenty or thirty years ago, in addition to an increase in financial flows since 2003. The question he raised was about the way in which these improvements have been used.

The degree of utilization of these inflows in order to have structural reform and in order to diversify the productive base has not been very strong in Latin America, Campodonico explained. In this regard, the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) considered that Latin America has lost the decade. Latin American countries have been mostly very complacent about this super cycle.

He also called for distinguishing between export-led growth that involves a big component of industrialization and state intervention, such as the practice in South East Asia and China, compared to export-led growth in Latin America that has been orthodox-based and focused on natural resources. The statistics show a de-industrialization of Latin America. UNIDO’s statistics show that Latin America diminished it values-added in manufacturing of developing countries from 35% in 1992 to 17% in 2010.

Besides cautioning of potential difficulties ahead, Dr. Campodonico pointed out that Latin America cannot be seen in one case or scenario and he addressed a few country cases that he considered successful in their policy choices. He discussed the cases of Bolivia and Costa Rica that he considered have fared very well. Dr. Campodonico explained that Bolivia undertook important reform with oil and gas companies over the last two or three years. Real GDP has been growing (6.7% in 2013) and the overall fiscal balance improving, at a consistent pace, and without current account deficits. In Costa Rica, policy has been oriented towards attracting innovation technology companies. Costa Rica has explicitly stated that they do not want to depend on raw materials for their growth.

Dr. Campodonico summarized that the revenues gathered in recent years from natural resources have mostly been already spent. There has not been inter-temporal funds or pension funds, like in Norway, and most of the revenues have been spent quickly in infrastructure and current flows. So the bonanza has already passed and has not been sufficiently taken into account, because the main framework of appreciation was expecting these trends to last many years. In the meantime, industrial policies were not instituted.

Dr. Campodonico concluded by referring to the technological revolution that the world is witnessing. He questioned whether these trends in technological innovations could create long-term cycles of economic growth and whether they would leave positive long-term implications on the economic situation.

Countries’ policies are based on self-interest

Dr. Charles Soludo, member of the South Centre’s board and former governor of Nigeria’s Central Bank, indicated in a general comment that in terms of the response to the crisis and lack of coordination, what has been witnessed is what one expects in the real world. This is despite what one would ideally wish for. Yet, he called for searching and identifying the countries and sectors where opportunities lie.

Dr. Soludo’s first point was that we live in a multi-polar world, and the categories of developing and advanced countries are no longer useful. Most problems, including that of unemployment and lack of jobs, poverty, climate change, energy, and inequality are faced by every country; the difference is a matter of the degree of the problem.

Dr. Soludo explained that although categories are still needed, it is important to realize that there are even least developed countries that have been achieving significant progress, for example seeing growth rates exceeding 7% over several years. There are countries getting by, while others are being left behind, he noted.

In regard to interconnectedness and intensifying spillovers, Soludo noted that trade as a share of GDP has gone up to around 35%, while capital flows intensified more than 4 times compared to 1995. Yet, the mechanisms of cooperation globally are limited, Dr. Soludo cautioned.

Increasingly, policy choices are serving narrow domestic interests and not designed taking into consideration the collective interests in a global context. Less than one percent of policy makers’ attention is focusing on issues we wish them to focus on such, as interconnectedness and spillovers, Dr. Soludo noted.

Dr. Soludo referred to an IMF calculation that showed that greater degrees of harmonization between the main economies of the world would lead to an increase in the global GDP of around 3% in the long run. Yet, reality is that democracies and domestic power bases in these countries make it impossible to respond in a way that reflects coordination and harmonization. In the end, every country resorts to self-help approaches, Soludo noted.

Dr. Soludo added that precisely at the time that the global system might need slightly inflationary policies to ensure speedy recovery, what we are getting is the reverse. This, he explained, is driven by domestic politics.

Besides few cosmetic changes, neo-liberalism is still alive and well, and dominates policy making everywhere, Dr. Soludo underlined. Recovery remains fragile and a new crisis remains probable or imminent, Soludo cautioned. It is a race to the bottom as each country seeks self-insurance, he explained. Part of this self-help is sought by the United States through the TPP and by the European Union through the EPAs, which represents a bail out sought from the African countries and ACP.

Soludo underlined the importance of China’s economy to many other developing countries. He noted that China has been considered as the new market, especially for countries dependent on commodities and oil, where much of their exports have been directed. Yet, the old model that propelled China’s growth seems to be going out of steam. The question is for how long can this approach continue, Dr. Soludo noted, and what would happen to a lot of these countries if China slows down.

Soludo was of the opinion that China may indeed need to live on bubbles for an extended period of time, especially for poorer developing countries that shifted their dependence to China to be able to continue to live. Otherwise, the greater and more devastating threat could be resulting from a slowdown in China. Dr. Soludo referred to that situation as the ‘threat from within’ in the context of South–South integration.

In terms of the outlook for countries that are increasingly left behind, Dr. Soludo referred to what he called the ‘paradox of poverty’. He explained that poor communities often have greater incentives to bond together, but also have greater resentment among them. So if some money trickles down or gets promised from the EU or another party, he noted, some countries are prepared to sell their regions and the entire coordination mechanism among them would then collapse.

Dr. Soludo cautioned that African countries could suffer from intensified levels of poverty and inequality in the next few years if their coordination vis-a-vis the EPAs falls out. This will lead to wiping out the limited manufacturing capacity in the region. He underlined that the aid promised to African countries is not additional and in fact has been declining. He added that Europe has its own crisis, and cannot support others.

In conclusion, Dr. Soludo noted that in a world with a dominant reserve currency, where policy makers are most of the time preoccupied with domestic welfare and hardly deal with global welfare, future crises happen to be almost an inevitable feature of the global economy as it is currently designed. However, Dr. Soludo stressed, not everyone will suffer in the same way.

Attempts to further constrain South’s policy space

Egypt’s Ambassador in Geneva, H.E. Mr. Walid Mahmoud Abdelnasser, agreed with previous speakers about the weakness of the international economy, which he saw still suffers from global imbalances and structural complexities. Several years after the onset of the financial crisis, Ambassador Abdelnasser noted, the world economy remains in a state of disorder. The burden of adjustment of the global imbalances, which contributed to the outbreak of the financial crisis, remains with the developing countries. In 2008 and 2009, there have been calls and willingness worldwide for urgent reforms of the international monetary and financial system, however, the issue disappeared from the international agenda, he recalled.

Ambassador Abdelnasser was of the opinion that the outlook for the global economy and for the international environment enabling development continues to be highly uncertain. The expansion of the world economy, though favorable for many developing countries, was based on unsustainable global demand and financing patterns, he added. Within this state of uncertainty and volatility of the international economic environment, the developing countries that adopted the export-oriented growth model began to suffer due to unilateral economic measures taken by some developed countries, he added.

Ambassador Abdelnasser stated that “development is not properly addressed in the international economic context”. He added that “there are attempts to divert the responsibility regarding development from the international scene to be confined only within the national levels, while ignoring the global imbalance and the international constraints that limit the policy space for the developing countries to identify their priorities”. As an example he mentioned the case of a developing country that would like to formulate industrial policy to enhance its productive capacity in an infant industry. He considered that such a country could be challenged by its international commitments stipulated in the multilateral trade agreements that often shrink the policy space required for development needs.

Ambassador Abdelnasser added that the attempts to further constrain this policy space are incessant. The developed countries are trying to establish norms that go beyond the development priorities of the South, he noted. Those attempts are clear in the multilateral negotiations in all issue-areas, including trade, climate change, intellectual property, investment, among others. In this context, the norm setting in various regimes focuses on establishing global rules and high standards without paying a real attention to the various developmental needs of the developing countries, Ambassador Abdelnasser cautioned.

For example, in the area of intellectual property, the focus remains on the protection and enforcement of intellectual property and not on the technology transfer and the equitable benefit sharing. It is ironic that some developing countries, such as India, are being criticized for formulating development-oriented intellectual property policy, Ambassador Abdelnasser stressed. In the climate change area, Ambassador Abdelnasser recalled the backtracking on the previously well-established principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’, whereby the developing countries are being asked to pay for the historical mistakes of the others.

In the area of trade, the Doha Development Agenda has not yet been implemented after 13 years of stalemate, and there is no certainty that the previously expected developmental gains will be harvested, Ambassador Abdelnasser noted. He stated that “instead, the narrative that is being promoted in trade policy is that globalization and interdependence are driven by Global Value Chains, and the only way for any country to secure its share in the Global Value Chains is through extensive trade liberalization”. However, he added, “this approach neglects the reality that the global imbalances made the distribution of shares in Global Value Chains entirely asymmetrical”.

Ambassador Abdelnasser recalled UNCTAD’s breakdown of the distribution of the global valued-added in 2013 using OECD-WTO database, which shows the following: 67% accrue to OECD countries, 8% from Newly Industrialized Countries I (Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea), 3% from Newly Industrialized Countries II (Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines), 9% from China, 5% for other BRICS (India, South Africa, Brazil, Russia), 8% for all other developing countries and LDCs. Those indicators clearly demonstrate the structural constraints faced by the small players within the Global Value Chains, Ambassador Abdelnasser stressed.

Ambassador Abdelnasser concluded that the global economy needs systemic reform to address the global imbalances. Furthermore, development must be placed at the core of the multilateral negotiations in all issue-areas.

Book Launch: Catch Up

A book launch of Catch Up, Developing Countries in the World Economy by Prof. Deepak Nayyar, Emeritus Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India and Vice Chair of the Board of the South Centre, was held in conjunction with the South Centre Conference held on 19 March 2014 in Geneva. Below is an abstract of the book.

The object of this book is to analyze the evolution of developing countries in the world economy, situated in a long term historical perspective, from the onset of the second millennium but with a focus on the second half of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century. It is perhaps among the first to address this theme on such a wide canvas that spans both time and space.

In doing so, it highlights the overwhelming significance of what are now developing countries in the world until 200 years ago to trace their decline and fall from 1820 to 1950. The six decades since then have witnessed an increase in the share of developing countries not only in world population and world income but also in international trade, international investment, industrial production and manufactured exports which gathered momentum after 1980.

The book explores the factors underlying this fall and rise to discuss the ongoing catch up in the world economy driven by industrialization and economic growth. Their impressive performance, disaggregated analysis shows, is characterized by uneven development. There is an exclusion of countries and people from the process. The catch up is concentrated in a few countries. Growth has often not been transformed into meaningful development that improves the wellbeing of people.

Yet, the beginnings of a shift in the balance of power in the world economy are discernible. But developing countries can sustain this rise only if they can transform themselves into inclusive societies where economic growth, human development and social progress move in tandem. Their past could then be a pointer to their future.

Comments on the book

`Essential reading for anyone who wants to get a balanced understanding of the history of the world economy. It offers a breath-taking historical sweep. A masterpiece. ´

-Ha-Joon Chang, University of Cambridge, author of Kicking Away the Ladder and 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism

`Nayyar analyzes lucidly the ongoing change and discusses forcefully the prospects for this great transformation, how it will be brought about, and what it will imply for the world order which will emerge.´

-Joseph Stiglitz, University Professor, Columbia University, New York, and Nobel Laureate in Economics

Africa’s acute problems with the EPAs

Ambassador Nathan Irumba, executive director of SEATINI, said that the greatest challenge facing Africa at this moment is the negotiations of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the European Union (EU). EPA negotiations have been going on since 2002.

Ambassador Irumba highlighted the interface among EPAs, the multilateral trading system, and regional integration. He explained that the relation of the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries with the EU was governed by the Lome and Cotonou conventions, whereby the ACP countries enjoyed non-reciprocal trade preferences. The relationship was based on three pillars: dialogue, development and finance, and trade. The Cotonou Agreement was judged to be incompatible with the WTO rules. At the Doha Ministerial Conference, the EU and ACP countries were granted a waiver with a view to making the agreement WTO compatible. The negotiations on that track started in 2002.

Ambassador Irumba explained that the objectives of the partnership between the EU and ACP countries include ensuring sustainable development, smooth integration in the global economy, and eradication of poverty. Principles enshrined in the partnership are sustainable development, reciprocity, and special and differential treatment (SDT). As the negotiations emerged, tension was revealed among these principles, specifically the principles of reciprocity and SDT, Ambassador Irumba noted.

In terms of reciprocity, which is one of the necessities of Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947) that addresses ‘Territorial Application – Frontier Traffic – Customs Unions and Free Trade Areas’, the question arises on what constitutes ‘substantially all trade’ on which duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce shall be eliminated for a free trade area to be considered compatible with Article XXIV.

Ambassador Irumba said that the EU Commission has taken advantage of the negotiations and Article XXIV of the GATT to pursue the ‘Global Europe’ agenda, whereas one would have expected the negotiations to be confined to minimum provisions that conform to the principles of the WTO. The approach under the ‘Global Europe’ agenda extends beyond the WTO requirements.

The EU Commission defined ‘substantially all trade’ as requiring liberalization up to 80% of trade by ACP countries, while the EU offered liberalization of 100% in return. That is considered quite deep liberalization, Ambassador Irumba underlined, and wondered whether it will be in the interest of African countries to undertake such liberalization.

It was noted by Ambassador Irumba that under the WTO negotiations on non-agricultural market access (NAMA), least developed countries (LDCs) and most African countries are not expected to undertake reductions under the proposed formula.

Another aspect highlighted by Ambassador Irumba is the whole question on the EU’s demand for prohibition or limitations on export taxes. The EU is worried about the appetite of China and India in regard to Africa’s raw materials, the Ambassador noted. African countries insist that they need export taxes. Yet, on the question of agricultural subsidies, the EU insists that this issue should be discussed within the WTO and should not be discussed within EPAs.

Another contentious aspect highlighted by Ambassador Irumba is the most-favored nation (MFN) principle, whereby he explained that the EU insists that any preferential treatment offered by African countries to emerging developing countries, such as India or Brazil, should be offered to the EU as well. Yet, under the WTO, trade among developing countries was supposed to be covered by the Enabling Clause (1979), he highlighted.

At all these levels, there is an attempt to go beyond what the African countries offered in the WTO and what the WTO requires.

Ambassador Irumba also discussed the question of the ‘rendezvous clause’, whereby the EU requires partner countries to commit to discussions on issues like intellectual property and trade facilitation. So far, there are no substantive negotiations on these areas, but the EU insists on a timetable in this regard, Irumba explained.