Downturn in Commodity Prices

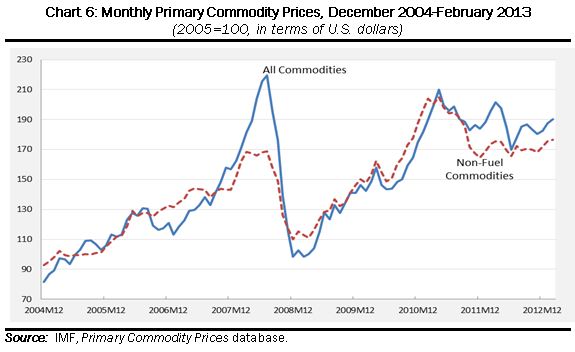

The financial crisis in Advanced Economies (AEs) has not depressed commodity prices to the extent seen in previous post-war recessions. The boom that had started in 2003 continued until summer 2008 with the index for all primary commodities rising by more than threefold (Chart 6). This was followed by a steep downturn in the second half of 2008, which took the index back to the level of 2004. But like capital flows and remittances, commodity prices also recovered strongly from the beginning of 2009, rising until spring 2011 when they levelled off and started to fall, manifesting increased short-term instability. In the early months of 2013, the index for all commodities was 15 per cent below the peak reached in summer 2008.

Different commodities that go into the aggregate index in Chart 6 are not only linked to economic activity in different ways, but have also important supply-side differences.Still, the behaviour of prices of commodity sub-categories has been broadly similar and highly correlated with global economic activity, particularly in Developing Countries (DCs), suggesting the dominance of common demand-side factors. Rapid growth in major commodity-importing DCs, notably China and to a lesser extent India, played a central role in the pre-crisis boom. Growth in commodity-dependent DCs also added to the momentum by creating demand for each other’s primary commodities. Prices increased along with the share of DCs in world commodity consumption. Oil demand from DCs is now as high as that from AEs, with China importing as much as the Eurozone (EZ) and twice as much as Japan. In metals, China alone accounts for more than 40 per cent of world demand.

The boom that started in 2003 and has generally continued except for a short-lived sharp downturn in 2008 is seen as the beginning of a new commodity super-cycle driven by rapid growth and urbanization in China (Farooki and Kaplinsky, 2011; Farooki, 2012). Historically such cycles are found to range between 30-40 years with amplitudes 20-40 per cent higher or lower than the long-run trend, with non-oil prices closely following world GDP (Erten and Ocampo, 2012).

After the outbreak of the financial crisis in AEs, the momentum in commodity prices has been kept up entirely by growth in the South, notably in China whose import composition changed rapidly from manufactures to commodities as a result of its shift from export-led to investment-led growth. As its markets in major AEs started to shrink in 2008, China introduced a large investment package, notably in infrastructure and property, pushing the ratio of investment to GDP towards 50 per cent. Since such investment is much more intensive in commodities, notably in metals, than exports of manufactures which rely heavily on imported parts and components from other East Asian economies, the shift from export-led to investment-led growth has led to a massive increase in Chinese primary commodity imports, which doubled between 2009 and 2011 compared to some 50 per cent increase in its manufactured imports (Chart 8). During the same period prices of metals rose by 2.4 fold, much faster than other primary commodities.

The downturn in commodity prices that started in 2011 has coincided with the slowdown in China and India. Given the credit and property bubbles and excessive debt and capacity generated by the 2008 stimulus package, China has been hesitant to respond to the slowdown with a similar package, allowing, instead, its growth to fall below 8 per cent for the first time for several years. The slowdown in China has been reflected particularly by a sharp decline in metal prices, by some 25 per cent between the beginning of 2011 and end of 2012, considerably steeper than declines in other commodities.

Because of increased financialization of commodities and growing interdependence between financial and commodity markets, the financial crisis has also generated considerable instability in commodity prices. The severe swings seen during 2008 had an important speculative component. Within the first 6 months of that year, the overall price index rose by some 35 per cent, followed by a sharp decline of 55 per cent in the second half of the year. No change in supply conditions or demand for physical commodities in such a short span of time can explain such a sharp swing. It was largely caused by rapid, self-reinforcing shifts in trading in commodity features triggered by rapid changes in expectations and sentiments around the collapse of Lehman Brothers, about the depth of the crisis and its possible impact on commodity prices.

Since 2011, the EZ crisis has had a strong influence on commodity prices not only by weighing on the demand from the region but also through financial channels. First, it has had a depressing effect on commodity prices by making the dollar stronger than it would have otherwise been. Second, it has added to commodity instability by triggering surges of entry and exits in markets for commodity derivatives. Like capital flows, commodity prices have become highly sensitive to news coming from the EZ.

The short-term outlook for commodity prices is highly uncertain not only because of possible supply-side disruptions, notably in energy and food, but also because of demand uncertainties. The latest projections by the IMF WEO (April 2013) are for continued declines in 2013-14 for both oil and non-fuel primary commodities. These are based on the assumption of no drastic change in conditions in two main economies strongly affecting commodity prices – China and the EZ. However, in both cases risks are on the downside, raising the possibility of steeper declines than is projected.