Financial Spillovers: Volatile Capital Flows and Currency Rates Cause Instability in the South

The financial crisis in Advanced Economies (AEs) has led to considerable instability of private capital inflows, yield spreads, equity prices and exchange rates in Developing Countries (DCs). The surge in capital inflows to DCs that had begun in the early years of the 2000s with sharp cuts in interest rates and rapid expansion of liquidity in AEs continued unabated in the early months of the crisis. However, the flight to safety triggered by the Lehman collapse led to a sudden stop and reversal, resulting in strong downward pressures on exchange rates and asset prices. Closer and deeper integration with major financial centres and rapidly growing gross asset and liabilities positions of DCs with the AEs intensified the transmission of financial stress to asset, banking and currency markets. The crisis also led to a contraction of credit in DCs due to cut-back in international bank lending and local lending by foreign banks’ affiliates in DCs as well as declines in inter-bank cross-border lending for funding by domestic banks (Cetorelli and Goldberg, 2010).

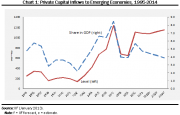

Although private capital inflows recovered quickly from early 2009, helped by sharp cuts in interest rates and quantitative easing (QE) in AEs and shifts in risk perceptions against them, they have lost their pre-crisis momentum and have become unstable and uneven. At the end of 2012, in nominal terms they were below the peak reached in 2007. As a percentage of GDP of the recipient countries, the decline was much steeper, from 8.5 per cent in 2007 to 4 per cent, a level not much different from those seen in the 1990s (Chart 1). Net flows available for current account financing and reserve accumulation in DCs are much lower, less than 1 per cent of GDP, because of resident outflows from DCs through direct and portfolio investment abroad. Institute of International Finance (IIF, January 2013) projections are for a moderate increase in 2013-14; but in absolute terms they are not expected to reach the 2007 peak and as a percentage of GDP they could continue to fall.

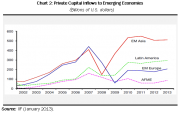

While the pre-Lehman boom in capital inflows was broad-based, pull factors have become more important in the post-Lehman recovery with lenders and investors increasingly differentiating among DCs. In absolute nominal terms net inflows to Asia and Latin America have exceeded the peaks reached on the eve of the global crisis even though the slowdown in China after 2010 has led to some deceleration in direct investment (Chart 2). By contrast, despite some recovery, inflows to European emerging economies have remained well below the peak reached before the crisis, largely due to strong fallouts from the Eurozone (EZ) crisis. This is also true for Africa and the Middle East.

The EZ crisis has played a central role in the overall weakness of private capital inflows to DCs. On the one hand, it has led to increased global risk aversion and greater preference for relatively safe assets. On the other hand, it has impinged directly on the volume of global capital flows. Before the outbreak of the global crisis, Europe was the main source of (gross) capital flows to the rest of the world, with $1600 billion per annum during 2004-07, higher than total outflows from the US and Japan taken together. With the outbreak of the crisis and the consequent bank deleveraging, total outflows from Europe fell sharply, registering a bare $300 billion a year during 2008-11.

The EZ crisis has also led to considerable short-term, month-to-month volatility in capital inflows to DCs as they have become increasingly sensitive to news coming from the region, leading to difficulties in macroeconomic management in DCs. From mid-2011, market sentiments turned sour with the deepening of the Greek crisis, strikes and political turmoil in the periphery and credit downgradings, leading to a drop in estimated capital inflows to DCs and significant downward revisions in forecasts.

Global risk appetite improved in the early months of 2012 with the agreement on European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and austerity packages in Greece and Spain, the implementation of the Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO), the signing of the Fiscal Compact and increased lending limits from the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the ESM.

However, markets became bearish again after spring 2012 when Spain requested assistance for bank capitalization, was downgraded by rating agencies and its yield spreads mounted, and concerns grew over Greece. As already noted, this was followed by renewed optimism after mid-2012 with the commitment of the European Central Bank (ECB) to save the euro. However, the mood changed again with the confusion created by the Cypriot bailout plan in March 2013.

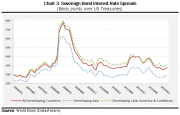

Changes in global risk appetite and private capital flows have also been mirrored by bond and equity markets of major emerging economies (Chart 3 and 4). After the Lehman collapse, sovereign bond spreads shot up and stood, at the end of 2008, above 800 basis points (bp), about three times the level in the previous year while the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) index fell to some 40 per cent of the level reached in 2007. With the recovery in capital flows, spreads fell and equity prices rose rapidly, but they both deteriorated after mid-2011 with the deepening of the EZ crisis. Despite some improvements in the second half of 2012, now spreads are above and the MSCI index is below the levels reached on the eve of the crisis.

The Lehman collapse and flight to safety also resulted in large drops in the currencies of most DCs against the dollar, with the notable exception of China (Chart 5). Many of them chose not to restrain the decline in view of weakened exports. Most DCs have welcomed the subsequent strong recovery in capital inflows and the boom in asset prices they helped to generate, but they have been ambivalent about their impact on exchange rates. The ultra-easy monetary policy in AEs has been widely seen as an attempt to achieve beggar-thy-neighbour competitive devaluations to boost exports to drive recovery in conditions of sluggish domestic demand. It was described as a currency war by the Brazilian Minister of Finance while the Governor of the South African Reserve Bank alluded that DCs were in effect caught in a cross fire between the ECB and the US Federal Reserve (Marcus, 2012).

DCs have responded in various ways. Initially, almost all countries had a hands-off approach to capital inflows. Many of them, notably in Asia, intervened heavily in foreign exchange markets, absorbing them in reserves and trying to sterilize interventions by issuing government and/or central bank debt. These countries avoided sharp appreciations. The total foreign exchange reserves of developing Asia increased by some $2200 billion during 2008-12 despite the decline in their overall current account surpluses. Others, particularly those pursuing inflation targeting, including Brazil, South Africa and Turkey, abstained from extensive interventions and hence experienced considerable appreciations.

There are two obvious reasons for this policy of non-intervention. First, since it is difficult to fully sterilize the impact of interventions on domestic liquidity, attempts to stabilize the currency would conflict with inflation targeting. Second, as most of these were high-interest-rate economies, sterilization would imply significant fiscal or quasi-fiscal costs, adding to government deficits and debt.

However, as upward pressures on the currencies of DCs persisted, several countries abandoned the hands-off approach to inflows and started using measures to control them. Interestingly the country that has made the most frequent recourse to such measures is Korea, a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and hence is subject to provisions of its Code of Liberalization of Capital Movements (Singh, 2010). The Korean won has been one of the weakest currencies in the entire post-crisis period. Its effective exchange rate has never gone back to pre-crisis levels, eliciting remarks that, together with the UK, it is the most aggressive “currency warrior” of the past five and a half years (Ferguson, 2013). The measures of control used by Korea include ceilings on forex forward positions of banks, a levy on non-deposit liabilities and a withholding tax on interest income from foreign holdings of treasuries and monetary stabilization bonds. Korea is now launching a $15 billion stimulus plan in order to support exporters facing pressures from a weaker yen and to revive growth, the third largest after those introduced in response to the 1997 Asian crisis and the 2008 global crisis (Kim, 2013).

After 2009 several DCs started to control capital inflows, mainly through market-friendly measures rather than direct restrictions. These included unremunerated reserve requirements (URR) and taxes (Brazil taxes on portfolio inflows; Peru on foreign purchases of CB (Central Bank) paper; and Colombia URR of 40 per cent for 6 months); minimum stay or holding periods (Colombia for inward FDI; Indonesia for CB papers); special reserve requirements (RR) and taxes on banks’ positions (Brazil RR on short positions and tax on short positions in forex derivatives; Indonesia RR for total foreign assets; Peru higher RR on non-resident local currency deposits); taxes and restrictions over borrowing abroad (India on corporate borrowing; Indonesia on bank borrowing; Peru additional capital requirements for forex credit exposure); and taxes on foreign earnings on financial assets (Thailand withholding tax on interest income and capital gains from domestic bonds). Some DCs such as South Africa liberalized outflows by residents in order to relieve the upward pressure on the currency.

These measures have been designed not so much to prevent financial fragility as to avoid currency appreciations and deterioration of the current account. As noted, not only have most emerging economies welcomed the boom in asset markets, but they have also ignored the build-up of vulnerability resulting from increased corporate borrowing abroad. However, the measures have not been very effective in limiting the volume of inflows as exceptions were made in several areas. In many cases the composition of inflows changed towards longer maturities and types of investment not covered by measures. Furthermore, taxes and other restrictions imposed were too weak to match arbitrage margins. Similar measures produced different outcomes in different countries because of differences in the implementation capacity and the sanctions attached to violation.

Although ultra-easy monetary policy has continued with full force after 2010, putting pressure on the currencies of some DCs, protests from the South became much less frequent. There are basically two reasons for it. From early 2011 most developing economies started to cool and hence the pressure of capital inflows on prices eased up. Second, the shift to domestic-demand-led growth has led to a widening of current account deficits in many major emerging economies, including Brazil, India, South Africa and Turkey, and this has increased the need for foreign capital and eased the upward pressure on currencies. Indeed, as seen in Chart 5, from mid-2011 the currencies of most of these countries started to weaken.

The so-called currency war among major AEs continues unabated. The ECB’s pledge to “do whatever it takes” to save the single currency, the announcement of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and a further interest rate cut by the ECB in May 2013 to bring it down to a record low of 0.5 per cent as well as the commitment of the US Fed to continue with the QE3 until unemployment fell below 6.5 per cent or inflation rose above 2.5 per cent suggest that the ultra-easy monetary policy in the US and the EZ are here to stay for some time to come. The Bank of Japan raised the inflation target in early 2013 and started a policy of aggressive QE, leading to a significant fall of the yen against the dollar and eliciting critical remarks, including from the Bundesbank president (Ferguson, 2013). In the UK, devaluations and exports have been seen as a way out of public and private deleveraging, with the government not ruling out abandoning inflation targeting. The pound sterling has depreciated in real effective terms more than any other major currency since August 2007. The Swiss National Bank has capped its currency against the euro and has been intervening heavily in order to prevent appreciation, despite a current account surplus of over 10 per cent of GDP.

However, liquidity expansion in AEs is not likely to lead to a generalized surge in capital inflows to DCs similar to that seen before the onset of the crisis although some countries favoured by international investors may experience strong inflows. First, in most emerging economies growth has slowed down sharply compared to the previous period. Secondly, interest rates have often been cut in response, thereby narrowing short-term arbitrage margins. In any case, a renewed surge in inflows of all types, including portfolio inflows, may be welcomed by several major DCs because of widened current account deficits.