Remittances Remain Stable

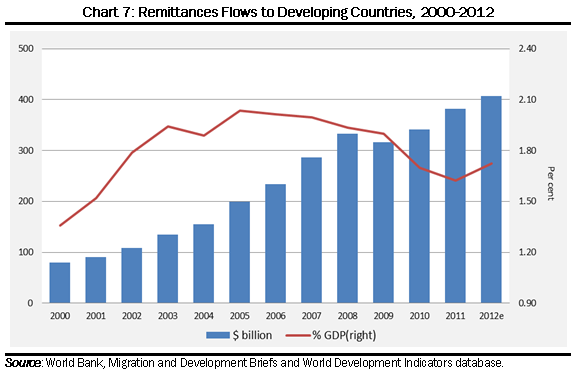

Worker’s remittances have emerged as a major source of external financing for Developing Countries (DCs) in the new millennium, second only to FDI inflows. They have followed broadly the same pattern as private capital inflows, expanding at a rate of 20 per cent per annum during 2002-08. They reached the peak of some 2 per cent of GDP of DCs taken together in the middle of the decade, mostly from migrant workers in the EU, followed by the US. For several DCs, they provided an important source of current account financing, at a rate of more than 3 per cent of GDP in India and Mexico and over 10 per cent in Bangladesh and the Philippines.

Surprisingly the crisis in the US and EU did not have a strong impact on total inflows of remittances to DCs even though these economies account for a very large proportion of total remittances and they have experienced sharp increases in unemployment after 2008. In nominal terms, remittances registered a small decline in 2009 followed by a moderate recovery afterwards, and are estimated to have reached $400 billion at the end of 2012. However, this has not been sufficient to reverse the decline in percentage of GDP of the recipient countries. At the end of 2012 they are estimated to have amounted to 1.7 per cent of GDP, compared to over 2 per cent during the pre-crisis peak (Chart 7).

Traditionally, remittances to DCs have generally served to support consumption of families and relatives in the countries of origin of migrant workers and financed mainly from their current earnings. However, existing statistical recording of these flows do not allow a precise determination either of the origin or of the final use of these transfers. They may actually be funded from accumulated savings of workers abroad and/or used in their countries of origin not for consumption but for investment in property or financial assets.

The continued increase in remittances to DCs after sharp rises in unemployment and declines in wages in the crisis-hit Advanced Economies (AEs) suggests that a greater proportion of these may have actually come from accumulated savings rather than current earnings of migrant workers. In the same vein, these might have been increasingly used for investment rather than consumption. In other words, they may be like capital flows rather than unrequited transfers. Increased rates of return on real and financial assets in DCs relative to AEs and the change of the risk perceptions against AEs may have encouraged such transfers. This has the implication that in the event of a shift in relative risk-return profiles of investments in AEs and DCs, these flows may well be reversed in the form of increased capital outflows from DCs.